Two years ago, I would not have anticipated or even believed that I’d be seeking an MBA today.

As someone who served in local and federal government prior to HBS, it would have been much more likely that I’d undertake a master’s degree in policy or law, but part of my personal thesis for going to business school was to go to where I was the weakest in order to learn the most. I craved new, rigorous skills, the vocabulary to unlock cross-sector collaboration, and time for professional development that some of my friends in traditional private-sector roles had gained. I was also personally compelled by the challenge of thinking differently or having to defend my stance in new ways, potentially to peers who may share a different worldview. What I didn’t anticipate, however, was just how directly relevant the MBA would be to my experiences in the public sector, and just how relevant my public sector experience would be in the classroom. The notion that a public-sector or impact-focused professional background would put me in an initially weak position turned out to be a false narrative that even I had subscribed to.

In the fall of our first year (RC), we take classes such as Technology Operations and Management (TOM), Finance, Marketing, and others. My first job out of college was a year-long Presidential Public Service Fellowship in the Mayor’s Office in Boston, partly funded by Harvard University to support pathways into public service upon graduation. In March 2020, halfway through my fellowship, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Boston and changed the trajectory of the entire experience. When crisis ensues and you are forced to shut down a city overnight – there’s no plan for that.

Who is drafting the press release, writing the OHR policy to send thousands of employees home, closing down Boston Public Schools in a matter of days with no chrome-books or hotspots, feeding the ~80% of students who are food insecure, securing PPE for Boston Fire, Police, and EMS during global supply chain shortages, coordinating with the governor and metro-area mayors to align and rewrite ever-changing guidance, helping small businesses access emergency funds or set up new revenue streams to stay afloat, setting-up mass testing and vaccination sites, ensuring the hospital system and homeless shelters have enough surge capacity, and coordinating private sector dollars flowing in for donations?

In TOM, we learned how to solve for process bottlenecks to improve the efficiency of the overall system and studied the Toyota Production System (TPS)’s real-world application in Texas during the pandemic, which made me recall navigating the logistics for our first testing sites in Boston. In Finance, we learned how to forecast out the expected returns of a project to decide whether it was a good investment to pursue – and again, it reminded me of how in coordination with the Governor’s Office and Army Corps of Engineers, we forecasted the cost/benefit of building the Boston Hope field hospital in the Boston Convention center based on hospital capacity rates, the daily data on new cases, and surge capacity needs. In Marketing, we learned the Roger’s 5 factors framework for explaining how new ideas or innovations are adopted, and while we didn’t use that vernacular in the City, we constantly thought about how to overcome vaccine hesitancy among historically undeserved communities, and how to increase adoption of new hybrid technologies and remote services in a time of immense uncertainty.

In the spring of RC year, we take classes on corporate accountability, international economy, and strategy – and there are countless examples from my time serving as a political appointee in Biden-Harris Administration before HBS that I could similarly map onto these classes, ranging from ensuring businesses are responsible for tackling child labor violations in the US and in their supply chains, executing the Administration’s Industrial Strategy from the workforce development perspective, and strategizing around the chess-game of policy and regulatory development. Unlike how we sometimes do in our class discussions, however, you cannot abstract away from the human impact of your decisions in government by using words of “efficiency” or “strategic positioning,” and the consequences of your actions are immense.

Ultimately, an MBA is about learning how to lead and manage in a changing world – a skill that I believe is industry and sector agnostic. While there has historically been a desire for private-sector expertise to solve social issues or lead innovation, I am starting to develop a new thesis around the opportunity to bring public-sector experience and human-impact focus to the private side of the equation while at HBS – and have been profoundly inspired by the swell of students, faculty, and efforts supported by the Social Enterprise Initiative who share the desire to use this degree for positive social change, which is so urgently needed.

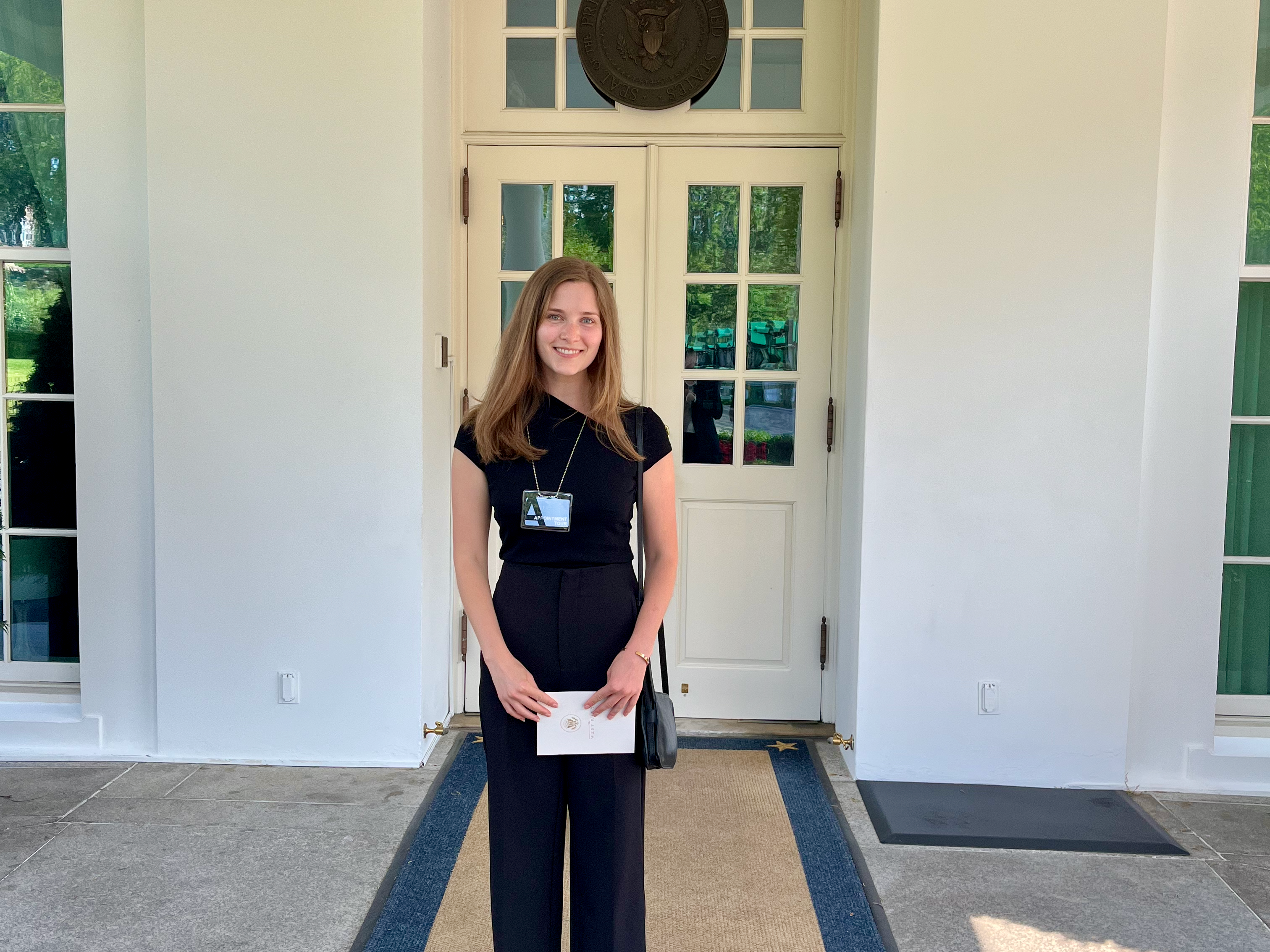

Kate Swain-Smith (MBA 2025) is a first-year MBA student and recipient of the Horace Goldsmith Fellowships, actively involved in the Social Enterprise Club, Social Enterprise Conference, and in the Social Enterprise Initiative’s Rising Leaders for Social Impact Forum.